ADHD has become one of the most discussed topics in schools, families, and adult psychology offices today. It is no longer just a childhood diagnosis. This attention and activity disorder continues throughout life: from the early school years, where a child cannot sit still, to an adult, whose mind is constantly spinning with dozens of thoughts and who rarely falls asleep without a fight.

The numbers only reinforce this reality. Global studies show that ADHD affects about 2-4 percent of children, and it is diagnosed in boys 4-5 times more often than in girls. However, the true extent of the disorder becomes apparent later: more than half of children retain symptoms into adulthood. In the adult population, ADHD is diagnosed in about 4.4 percent of people, and as many as 70 percent of them experience insomnia or other sleep disorders. Sleep is the invisible artery that feeds or balances all other aspects of ADHD.

However, we rarely talk about sleep in the context of ADHD. Yet it is often the barometer that most accurately shows how a person is feeling and how severe the main symptoms are.

When the body wants to rest, but the head doesn't

Most children and adults with ADHD describe their evenings similarly: the body is tired, the day is long, but the mind is in high gear. While many people are curling up in bed, a person with ADHD experiences the opposite effect – the second round of the day begins in their head. Thoughts are jumping, ideas are flowing, emotions are heightened, and the body does not want to give in to the rhythm dictated by society.

Parents see it as a “never-ending game” or “a hundred questions before bed.” Adults describe it more simply: “my head won’t turn off.”

Scientific observations only confirm these stories. People with ADHD are more likely to have delayed melatonin release, which means that natural sleepiness comes later. They fall asleep more slowly, wake up more often during the night, and their sleep is more fragmented. Even in children who do not have formal insomnia, studies often record “subclinical” sleep disturbance – sleep that is physically prolonged but not qualitatively refreshing.

This is precisely what causes the so-called social "jet lag" - the feeling when your internal clock is constantly lagging behind the social rhythm. In the morning you need to be alert, even though it's still night for your body. In the evening - yawn, even though your thoughts have just started sprinting.

Interestingly, some people with ADHD have the opposite rhythm. They go to bed very early, wake up with the first light of dawn, and live in a different time zone for a couple of hours. This is also ADHD, just a different expression.

Why is there so much insomnia in the ADHD world?

Sleep is not only a physiological but also a neurological system. In the case of ADHD, its basis lies in the brain: it is believed that disorders of dopamine and norepinephrine metabolism lead to faster mental "fatigue", but also make it difficult to switch from active to rest mode.

Scientific evidence shows that:

• about two-thirds of people with ADHD have delayed sleep phase type – their internal clock is naturally delayed;

• about a third have insomnia without circadian rhythm disorder;

• ADHD is often associated with variations in the CLOCK gene, which is responsible for the biological clock;

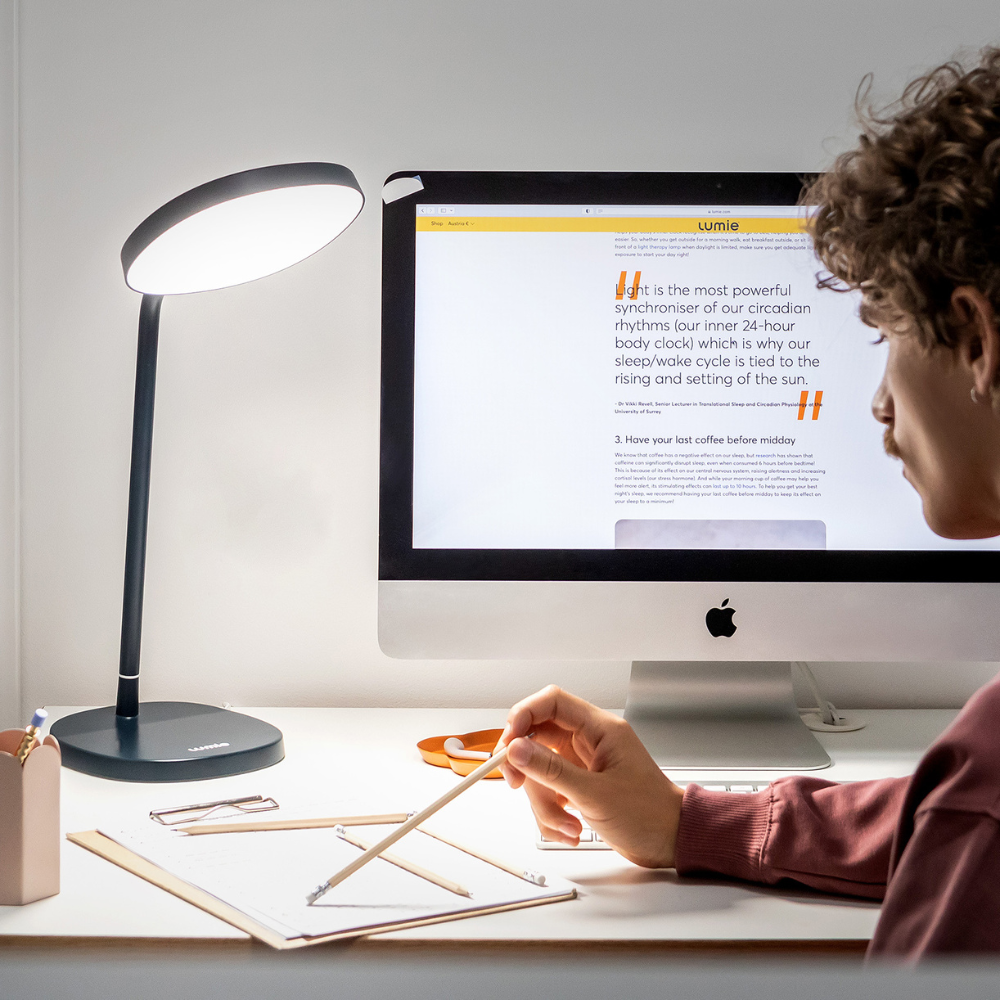

• even ordinary evening light from lamps or screens suppresses melatonin much more strongly in people with ADHD than in others.

When we put these factors together, it becomes clear why ADHD and sleep are so closely linked and why we have ignored this topic for so long.

A new perspective: how simple glasses in the evening can help reset your internal clock

In recent years, researchers have been looking for solutions that are non-invasive, affordable, and effective. One such solution is blue light-blocking sleep glasses. Sounds simple? It is. But the impact is much more profound than it might seem.

The study you shared, conducted at Western Psychiatry University, looked at how adults with ADHD responded to a two-week intervention in which they wore special glasses at night that filtered out blue light. The results surprised even the researchers themselves.

The study showed that even when participants didn’t fully follow the instructions, their sleep quality improved significantly. Their overall sleep quality score dropped from an average of eleven points (indicating a clinically significant sleep disturbance) to about four, below the threshold for insomnia. That means one thing: their sleep went from disturbed to within normal limits in just two weeks.

The link between light and ADHD was very clear here. Participants woke up less at night, felt more rested in the morning, and their anxiety levels dropped so dramatically that it was recorded by psychological assessment methods. Even more interestingly, those whose sleep was shifted the most to the late part of the day saw their bedtimes move up by as much as 40 minutes.

This is not just a small change. In the field of circadian rhythm, a shift of this magnitude is considered very significant.

Although the study participants only wore the glasses for an average of about two and a half hours per night (the recommended three), the effect was still significant, suggesting that light filtering may be one of the most affordable and simple ways to regulate sleep for people with ADHD.

What can we say about ADHD and sleep today?

ADHD is not just a behavioral or concentration challenge. It is a whole world that a person carries within themselves. Sleep in this world is not a luxury or an additional desire, but a necessary condition for the brain to function harmoniously. When you manage to bring order to the night rhythm, the daytime rhythm often improves: it is easier to concentrate, it is easier to manage emotions, it is easier to maintain a steady pace.

And sometimes all it takes is a small push - reducing the brightness of the screens, creating a darker environment, and simply putting on glasses that allow the brain to gradually switch to rest mode.

Perhaps the paradox of our time is that the smart technologies that have brought so much light into our lives have also stolen part of our night. And now, simple, orange-tinted glasses are quietly helping to bring that night back.

And when a person with ADHD finally wakes up in the morning feeling like they actually slept, a completely different day opens up. Calmer. Clearer. It feels that way until the evening, when the small but extremely important ritual of getting ready for sleep begins again, which no longer becomes a struggle, but a natural transition to peace.